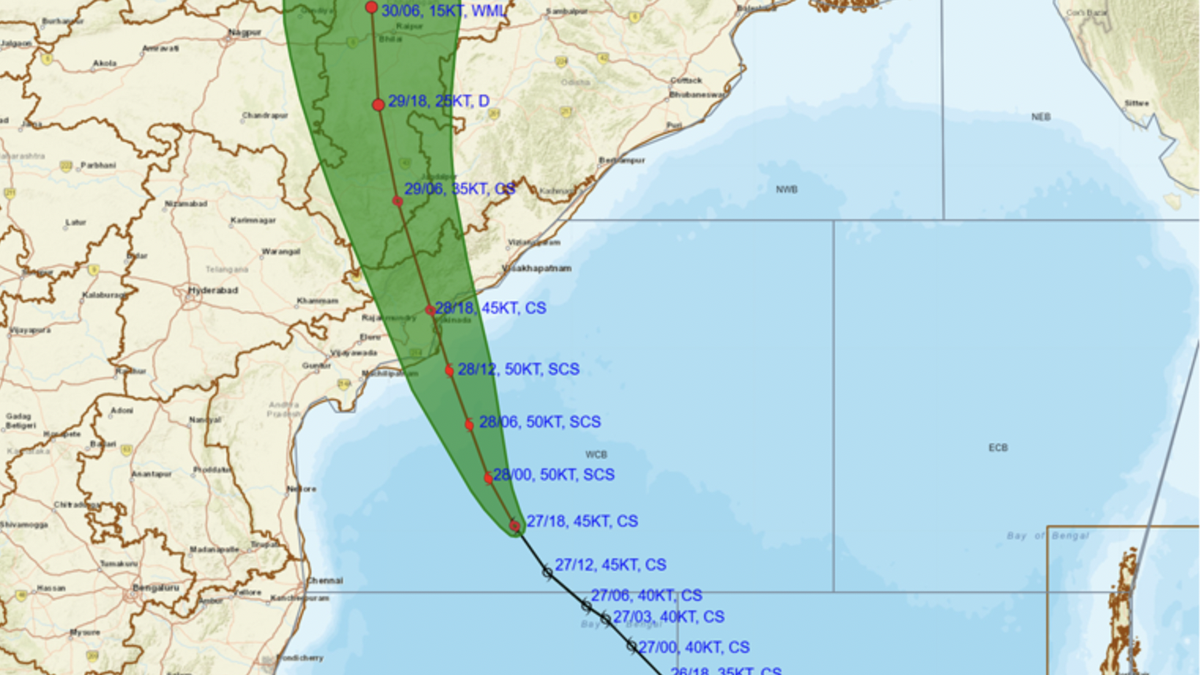

Observed (black line) and forecast track of Cyclone Montha at 11.30 pm hours on October 27, 2025. The green area depicts the cone of uncertainty.

| Photo Credit: India Meteorological Department

Tropical cyclones are carried by the large-scale wind patterns that govern the atmosphere. These storms form over warm ocean waters, where the sea surface temperature is about 26º C or more, providing the heat and moisture they need to grow. But once they have formed, the way they move depends entirely on the winds that surround them, much like a leaf swept along by a river.

The tropical areas where cyclones develop are roughly between 5º and 20º north and south (of the equator). Here the dominant winds are the trade winds, which blow from east to west throughout the year as part of the global Hadley circulation. This is a global convection pattern driven by the uneven heating of the earth: warm air rises near the equator, moves towards the poles, cools and sinks around the 30º latitude, and then flows back towards the equator at the surface. Because the earth rotates, the returning air is deflected towards the west by the Coriolis effect, creating the easterly trade winds.

These winds thus tend to push storms westward across the oceans, which is why tropical cyclones in the Bay of Bengal move towards India’s east coast. It’s also why tropical storms in the Atlantic Ocean move from the African coast towards the Caribbean and the Americas and why those in the Pacific Ocean often head towards Asia and Australia.

While tropical cyclones draw their energy from warm ocean waters and can thus become more intense as long as they remain offshore, the winds don’t give them a choice. And as the storm moves, it may also encounter other atmospheric systems, such as mid-latitude westerlies farther north, which can alter its course. Sometimes these changes steer a storm harmlessly into open water — but it’s often the case that the prevailing flow carries the storm over land.

In December 2023, because the steering winds over the Bay of Bengal were weak, Cyclone Michaung moved very slowly and lingered for many hours offshore before making landfall.

If the global geography were reversed or if the trade winds blew the other way, cyclones would instead be carried out over open water and rarely make landfall.

A question obviously arises here: why then would a cyclone in the Arabian Sea make landfall over the west coast of India? Shouldn’t it move towards the Arabian Peninsula or the Horn of Africa instead?

If the trade winds were the only influence, then yes, storms in the Arabian Sea should indeed drift towards the Arabian Peninsula or Africa. But in practice, they often move towards India instead because of the monsoons.

In the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans, the trade winds blow consistently westwards, but in the Indian Ocean, the surface winds reverse directions with the monsoons. From around June to September, the southwest monsoon dominates: winds blow from the southwest towards the northeast. This means that during the monsoon and its onset and retreat phases, the low-level steering flow over the Arabian Sea often points towards India rather than away from it. Cyclones forming in this period thus are carried northeastward and make landfall along India’s western coast, particularly Gujarat, Maharashtra, and sometimes Kerala.

Outside the monsoon season, during winter and early spring, the circulation reverses: the northeast monsoon brings dry air from the Indian subcontinent towards the equator and Africa. So cyclones that form then are more likely to drift westwards towards the Arabian Peninsula or Somalia. However, a cyclone is also unlikely to form at this time because the waters are cooler and wind shear is stronger.

Published – October 28, 2025 09:00 am IST