It was 14 November 1969. For the world’s greatest player, it wasn’t the best penalty. More an untidy scuff into the bottom corner. But it was enough for Pelé and his Santos team to open the scoring in a 3-0 friendly win over lowly Botafogo da Paraiba. More importantly, it marked the great man’s 999th senior goal. Or did it?

Five days later, Santos travelled to Rio de Janeiro to face Vasco da Gama in a cup game and it seemed as if the entire nation was jammed into the cavernous Maracanã to witness a piece of football history. Despite a tropical rainstorm, every TV station, radio network and newspaper elbowed their way along the touchline waiting for the magic moment to happen.

It duly arrived in the 78th minute and, disappointingly, it was another penalty. This time Pelé casually stroked it into the right corner. Nothing spectacular, none of the supernatural grace, style and balance he was so famous for, but it was still celebrated as if Brazil had won the World Cup.

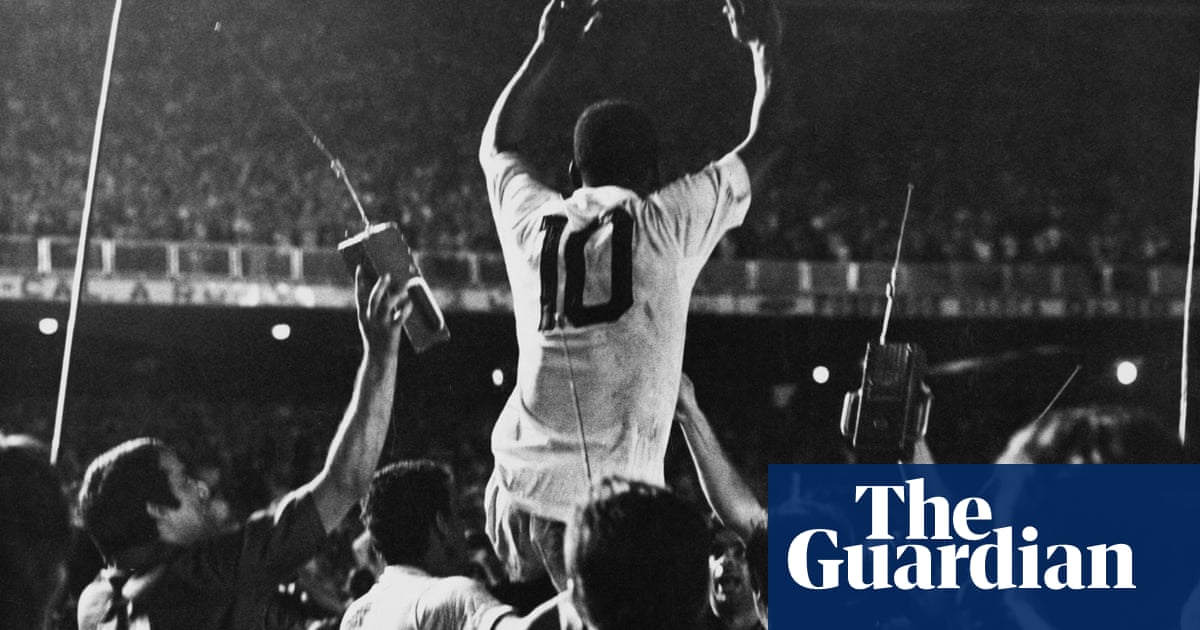

Santos won the game 2-1 but no one in the 80,000 crowd seemed to care. As the final whistle blew, thousands poured out of the stands and the great man was paraded around the pitch and carried off shoulder high. The celebrations in Rio lasted days and the achievement merited equal billing on the Brazilian front pages to Apollo 12’s landing on the moon.

It was Pelé’s 1,000th career goal. Or was it? More than a quarter of a century later a Brazilian journalist tried to tidy up the somewhat chaotic statistics around Pelé’s career and, horror of horrors, he discovered a lost goal.

Somehow, the records had failed to register a goal scored by Pelé in Brazil’s 4-1 win over Paraguay in a South American military cup competition in 1959. The recalibration that followed meant his 1,000th goal was scored in the game against Botafogo da Paraiba and not the one wildly celebrated in Rio at the Maracanã.

It was hardly a shock the records appeared unreliable. After all they had been derived not only from myriad internationals, but from a confusion of local, state and national games, as well as scores of obscure friendlies played across the globe. In those days Santos would play anyone – seemingly anywhere – for a big bag of cash and decent expenses, so keeping accurate records was not an exact science.

Diego Maradona put it best while discussing the 1,000 goals on a TV chatshow with Pelé some years ago, asking him, tongue firmly in cheek: “Who did you score them against, your nephews in the back yard?” More recently, and with far less humour, Cristiano Ronaldo charmlessly suggested that when he hits his 1,000 goals at least they would all be on video.

Pelé was typically phlegmatic about the whole thing. In a 1995 interview he said: “Thank goodness the controversy is not about deciding whether or not I scored a thousand goals. For me it doesn’t matter whether I scored my thousandth goal against Vasco or not. It’s already been done.”

However, for one man it meant a great deal. Rewind to 1969 and when Pelé and Santos arrived in the remote north-eastern city of João Pessoa, for that Botafogo game, a local councillor, Derivaldo Mendonça, presented him with the key to the city, smartly negotiating that Pelé would, in return, hand him his shirt after the game.

That’s where things became a little strange. Shortly after Pelé scored the 17th-minute penalty, the Santos keeper suddenly became rather theatrically sick and, much to the annoyance of the 20,000 crowd, Pelé replaced him in goal, ensuring he didn’t score his 1,000th goal in the middle of nowhere and, so the cynics maintained, reserving the moment for the game at the national stadium. Before he went between the sticks, Pelé ran across to the touchline and handed over his shirt, telling Cllr Mendonça: “There’s your jersey Mr Councillor. Thy will is done.”

For years the white No 10 shirt stayed in the family and when the records changed, he realised he now had the shirt from when the 1,000th goal was scored – and not the 999th.

after newsletter promotion

It is this shirt, now owned by the Steve Santos Barlow, a friend of the Mendonça family and who watched the game in João Pessoa as a 10-year-old, that will be the centrepiece of a big football auction, organised by Hanson World Football, at Wembley on 10 April.

Estimates suggest it will fetch anything up to £500,000, far exceeding his World Cup final-winning shirts of 1958 and 1970, which sold for £70,000 and £157,000, respectively, in the early 00s. But it’s likely to remain a long way from the record set by the sale of Maradona’s shirt worn during the second half of the “Hand of God” World Cup quarter-final between Argentina and England. That sold a few years ago for more than £7m, while Lionel Messi’s six shirts from the last World Cup went for more than £6m in 2023.

The most expensive sporting shirt is Babe Ruth’s 1932 World Series-winning New York Yankees jersey, from the game when he pointed to the stands before smashing a home run. It went for just over $24m (£18.5m) last summer.

The provenance of Pelé’s Santos shirt is undeniable, though the mathematics of his career remain a good deal murkier. There are those who suggest half his goals were scored in non-competitive games. But the Guinness Book of Records still recognises his official career total as an extraordinary 1,279 goals in 1,363 matches. There was even a report in a 60s football magazine suggesting the record was 150 goals short, because it was missing all the goals scored by Pelé for his junior team between his 14th and 16th birthdays – the age he joined Santos.

Whatever it all adds up to, Pelé’s place in the pantheon of the world’s greatest players is assured and his unwashed, mud- and sweat-stained shirt remains a unique piece of football history likely to register another set of stratospheric numbers.