(This article forms a part of the Science for All newsletter that takes the jargon out of science and puts the fun in! Subscribe now!)

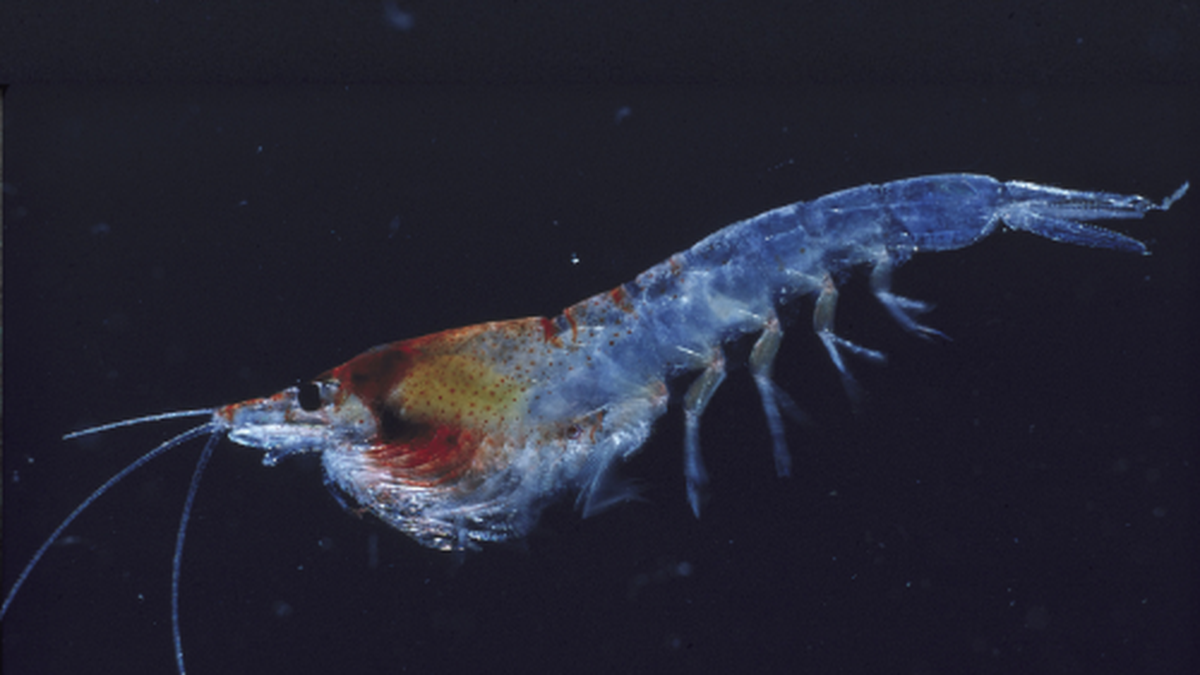

Krill (Euphausia superba) are transparent marine organisms. Each krill is the size of a matchbox but they travel the open seas in swarms of several thousands. They are prey to millions of seals, penguins, and whales in the Southern Ocean, a rapidly warming water body whose temperature has significant effects on tropical rainfall.

All organisms have an internal clock called the circadian rhythm that syncs with the day/night cycle. If the natural cycle is interrupted, so is the rhythm. This is why you have jet lag. Yet krill have been found to have a circadian rhythm that ticks on even when their days and nights are distorted.

Researchers from Germany and the U.K. recently reported this finding in eLife.

Every day, krill move to the surface of the ocean and back down to feed and fend off predators. This collective swimming is called diel vertical migration (DVM). They tend to move towards the surface at night and to the depths during the day.

The study took a closer look at the mechanism that drives DVM.

“We know that krill move up and down in the water column each day which also has important implications on nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration, but we don’t know what mechanism governs this behaviour. This study sheds light on that, and will help us better understand and conserve this incredible species,” Matthew Savoca, a research scientist at the Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University and who wasn’t involved in the study, said.

In 2024, the team developed a device called Activity Monitor for Aquatic Zooplankter (AMAZE). It’s an observation incubator with 80-cm-long acrylic glass columns. Laser light is passed through the columns. When krill swim through them, they interrupt the laser light, which a detector records to track the krill’s movement.

For the experiment, the researchers collected krill from the Bransfield Strait and the South Orkney Islands located about 800 km and 1,250 km southeast, respectively, from the bottom tip of South America.

They divided the samples into two groups. The first was immediately transferred to AMAZE, which simulated the natural durations of day and night around the islands. Some days were short (5.5 hours) and others much longer (15 hours). Then the krill were placed in complete darkness for 4-8 days.

The scientists observed the second group of kill in their natural conditions using hydroacoustics, then they were moved to AMAZE and kept in darkness. Researchers studied the second group in conditions corresponding to the four seasons.

Krill’s DVM activity increased towards the night and decreased during morning hours. Notably, the scientists found that when DVM began or ended was fixed to daytime and nighttime whenever they happened, rather than to particular hours of the day. In fact the krill maintained the same DVM patterns even in complete darkness.

If the days were long, the krill fed for fewer hours. And if nights were longer, they fed for longer and in phases.

As krill move across the ocean via currents, they influence the lives of many other creatures around them.

Lukas Hüppe, a doctoral researcher at the University of Würzburg in Germany and coauthor of the study, expressed optimism about the findings’ implications for the Southern Ocean ecosystem, which centres around this species.

“The findings provide novel insights into the mechanistic underpinnings of daily and seasonal timing in Antarctic krill, a marine pelagic key species, endemic to a high-latitude region,” the researchers wrote in their paper. “Mechanistic studies are a prerequisite for understanding how krill adapt to their specific environment and their flexibility in responding to environmental changes.”

Manaswini Vijayakumar is interning with The Hindu.

From the Science pages

Question Corner

Flora and fauna

Published – June 18, 2025 01:34 pm IST