From bones to immune cells, vitamin D is everywhere, guiding growth and shaping defence. But could it also have an effect on the mind?

A major new study suggests so. Published in The Lancet Psychiatry, the study drew from the extraordinary depth of Danish health data to establish whether neonatal vitamin D levels might contribute to psychological and neurodevelopmental conditions.

What the study found

Researchers at Aarhus University in collaboration with the Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen used dried blood spot samples from 88,764 individuals born between 1981 and 2005 — part of a universal neonatal screening programme that stores nearly all newborns’ blood in the Danish Neonatal Screening Biobank.

From these samples, the team measured levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, or 25(OH)D, which is the standard marker of vitamin D status, and vitamin D-binding protein, which carries vitamin D in the blood and prolongs its activity.

Using nationwide Danish health registries, the researchers tracked which individuals developed major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder or anorexia nervosa — and asked whether their vitamin D levels at birth were linked to these outcomes.

The results were striking. Babies with higher vitamin D levels were less likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, ADHD or autism. Newborns with levels about 12.6 nmol/l higher than average had an 18% lower risk of schizophrenia, 11% lower risk of ADHD, and 7% lower risk of autism. Vitamin D-binding protein levels were also linked to schizophrenia risk.

To understand the broader public health impact, the researchers modelled a scenario in which every baby had vitamin D levels in the top 60% of the sample. In that case, they estimated that 15% of schizophrenia cases, 9% of ADHD cases, and 5% of autism cases might have been prevented. These effects appeared early, with children who had higher vitamin D levels showing lower risk from a young age.

The lack of association with depression or bipolar disorder, the authors suggested, may reflect both the later onset of these conditions in life and the possibility that neonatal vitamin D plays a more central role in early neurodevelopmental pathways than in mood disorders.

Testing plausible causality

Observational studies, especially in nutrition, often face two big problems. One is reverse causation, where what looks like a cause is actually an early effect. For example, early brain changes might influence how the body handles vitamin D, making it look like vitamin D is the cause when it’s actually an effect. The second is confounding, where a third factor like a mother’s diet or immune health influences both vitamin D levels and the child’s risk of mental illness.

To check for these biases, the researchers turned to genetics. They started with the polygenic risk score (PRS), which looks at many small inherited differences that alter a person’s vitamin D levels and generates a score. They found that individuals with higher PRS scores for vitamin D were less likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, ADHD or autism.

PRS also helped rule out reverse causation since a child’s later psychiatric diagnosis can’t influence the vitamin D genes they were born with.

However, PRS couldn’t fully resolve confounding: where some variants might still influence other traits beyond vitamin D. Perhaps a gene variant perturbing vitamin D levels also alters neurodevelopment?

As Upasana Bhattacharyya, a scientist at Northwell Health in New York, explained: “While PRS can suggest a biological link, they mainly capture variants that are associated with a trait — not necessarily ones that cause it.” She added that PRS typically uses variations that are related to many other functions as well, thereby establishing associations without directionality.

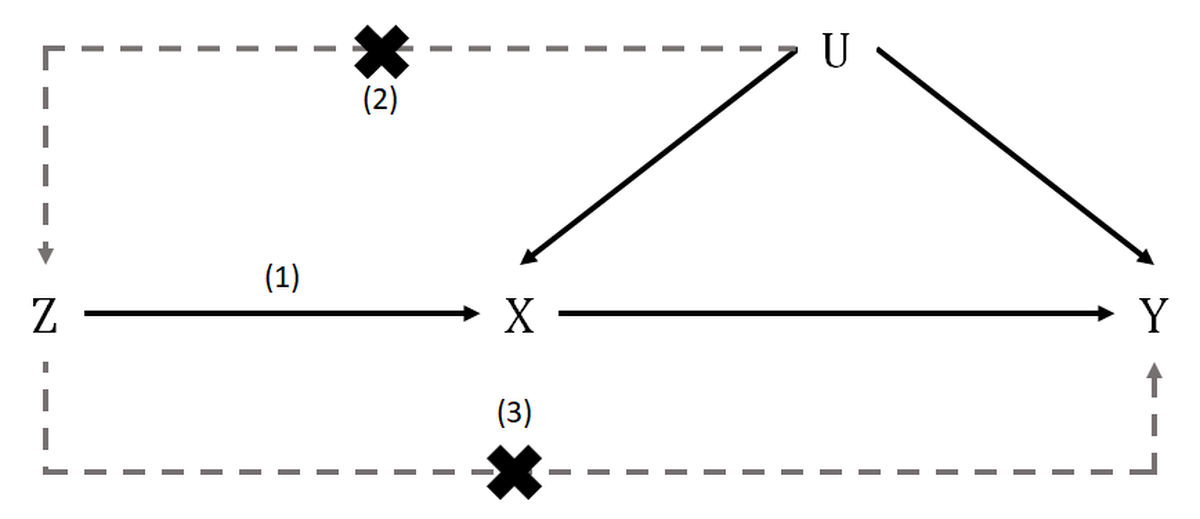

To test for a more direct effect, the researchers turned to Mendelian randomisation, a method that uses genetic variants that have a stronger effect on vitamin D levels. If people who inherit variants that raise (only) vitamin D levels consistently have a lower risk of schizophrenia, ADHD or autism, it will be stronger evidence of a causal relationship between vitamin D levels and the risk of developing these conditions.

A schematic representation of Mendelian randomisation and its core assumptions. Z are the genetic variants, X is the exposure, Y is the outcome of interest, and U are possible confounding factors.

| Photo Credit:

Kaitlin Hazel Wade (CC BY-SA)

The researchers used two levels of Mendelian randomisation. First, they tested whether genetic predictors of vitamin D were associated with lower risk of psychiatric conditions. Then they examined two specific genetic variants in the GC gene, which regulates levels of vitamin D-binding protein in the blood. Together, they suggested that higher vitamin D levels may play a protective role, particularly in lowering the risk of ADHD and possibly schizophrenia and autism.

What the findings don’t mean

While the study used powerful genetic tools to test for causality, the authors have cautioned that some important uncertainties remain. Some gene variants might influence both vitamin D and brain development independently, a phenomenon known as pleiotropy. And because vitamin D was measured only at birth, the study couldn’t pinpoint which periods in pregnancy were more critical.

Second, if deficiency begins in the womb, it makes sense for intervention to begin there, too. However, a 2024 randomised controlled trial in Denmark found that high-dose vitamin D supplementation (2800 IU/day) starting at pregnancy week 24 had no significant effect on the risk of autism or ADHD in children.

But such results also depend on timing, dosage, and whether mothers were actually deficient to begin with. In short, while vitamin D may not be the sole or dominant factor shaping neurodevelopment, it remains a plausible piece of a larger, complex puzzle.

Another key limitation was that nearly all participants were of European ancestry. In a smaller non-European group, the results were less consistent — possibly due to lower vitamin D levels, smaller sample size, and/or genetic diversity.

For these reasons, the researchers concluded that while their findings support a causal link, they can’t yet prove it outright.

India’s vitamin D problem

Sunlight is abundant in India but vitamin-D deficiency is rampant, and the findings carry especial weight here. A study conducted at AIIMS Rishikesh between 2017 and 2018 found that 74% of infants and 85.5% of their mothers were deficient in vitamin D, with nearly half experiencing severe deficiency. Another study from Bengaluru observed that 92.1% of newborns were deficient.

During pregnancy, the mother’s body undergoes a complex set of hormonal and metabolic changes to supply calcium for the developing foetal skeleton. These changes intensify in the third trimester as the skeleton grows rapidly. To meet this need, the mother’s intestines absorb more calcium, her kidneys excrete more, and her levels of active vitamin D rise to roughly twice their pre-pregnancy levels.

Despite these adaptations, maternal vitamin D levels don’t rise unless sunlight exposure or dietary intake improves. This is why even well-nourished pregnancies in India can result in deficiency. Sunlight alone isn’t always enough.

Evidence from Indian hospitals has also shown that a mother’s vitamin D status directly shapes her baby’s. A 2024 study conducted in the Bundelkhand region of India found a strong positive correlation between mothers’ and their infants’ vitamin D levels and interpreted it to mean babies born to vitamin D-deficient mothers were very likely to be deficient themselves.

This reinforces the idea that vitamin D insufficiency is not just an individual issue: it is a biological legacy passed from one generation to the next, shaping not just bones but, as the Danish study suggests, brains too.

These findings align with clinical experience in India. According to Anuradha Kapur, principal director of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at a Max Smart Super Speciality Hospital in New Delhi, timely supplementation in deficient mothers can remarkably improve both maternal and neonatal levels.

In her practice, she said high-dose therapy — typically of 60,000 IU per week in the third trimester — has been effective and safe, with clear benefits in infant growth and immunity. A small Indian trial last year echoed these findings: babies born to supplemented mothers had significantly better vitamin D levels at birth. By six months, none had developed severe deficiency, compared to more than half in the control group.

Caution rather than alarm

The growing evidence of vitamin D’s role in neurodevelopment strengthens the case for routine antenatal supplementation, experts say.

| Photo Credit:

AFP

The Danish study adds to growing evidence that early-life exposure, including nutrition, can shape long-term mental health. Vitamin D is no magic bullet, but through the right window, it might tilt the odds.

Dr. Kapur noted that routine vitamin D screening during pregnancy remains uncommon across much of the country. While some obstetricians in urban areas do test high-risk pregnancies, cost and lack of awareness continue to limit uptake in rural and semi-urban settings. As a result, many deficiencies go undiagnosed, especially when symptoms are subtle or overlooked during pregnancy.

She argued that India needs to shift from reactive treatment to preventive care. The growing evidence of vitamin D’s role in neurodevelopment, she said, strengthens the case for routine antenatal supplementation, ideally beginning as early as the first or second trimester.

“This is not about alarm,” Dr. Kapur said, “but about recognising that early brain development is shaped by access to nutrients — and vitamin D is one such modifiable element we can and must intervene on.”

Anirban Mukhopadhyay is a geneticist by training and science communicator from Delhi.