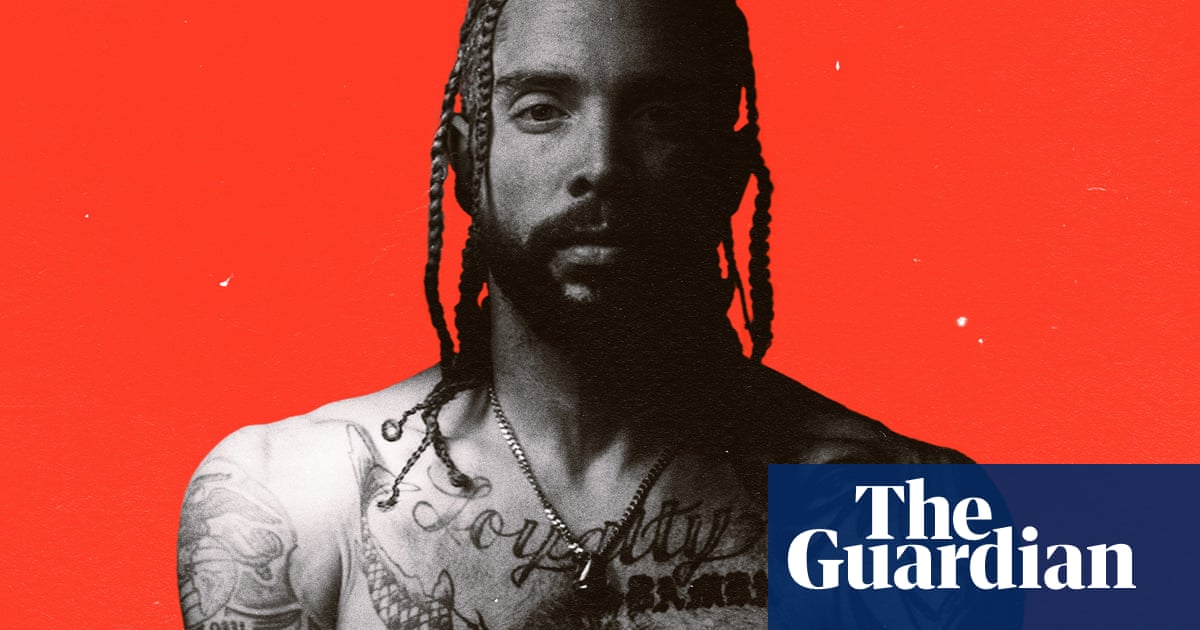

As 2023 drew to a close, Paul Bamba was a marginal club fighter with a record of five wins and three losses, compiled against mediocre opposition. Then his career changed in a very strange way. Bamba fought 14 times in 2024 and won all 14 of those fights by knockout. On 21 December 2024 he was credited with defeating Rogelio Medina Luna in a fight for the World Boxing Association ‘gold’ cruiserweight championship when Medina quit on his stool after the sixth round.

Bamba was living his dream. But the dream appears to have been a fantasy built in significant measure on fixed fights.

Six days after fighting Medina, Bamba was dead.

More than two dozen people have been interviewed for this story. Some of them asked that they not be mentioned by name out of concern that it could damage professional relationships. Others had no such reservations. The cautionary tale of Paul Bamba follows.

Bamba was born in Puerto Rico on 15 August 1989. His early years were mired in horrible deprivation that – he later told friends and posted on social media – led to his being taken from a crack-addicted mother when he was four years old. He never knew his biological father. He was moved from foster home to foster home before enlisting in the US Marines at the age of 17. He served in Iraq, left the military when his tour of duty ended, and, at 19, reunited with a man named Ismael Bamba who had befriended him when they were stationed together in San Diego.

Ismael Bamba is a career military officer, now a sergeant-major in the Marines stationed in South Korea. He and his first wife are from Ivory Coast. They separated in 2006 when their daughter, Linda, was nine. Linda joined the military in 2019 and is now a paralegal with the Judge Advocate General division (Jag) of the US Air Force. She will enter law school this fall and return to Jag as an attorney when her studies are done.

“My dad took Paul under his wing when Paul got out of the service,” Linda says. “Then he remarried and Paul moved in with us in San Diego. It was the first time Paul had ever been in a cohesive family unit. He was valued and had a home. That meant a lot to him.”

Ismael Bamba had 17 brothers and sisters. “Paul was the only light-skinned one in the family,” Linda says. “But everyone took to him. He was the family favorite. Later, my dad had a son with his second wife. So there was Paul, myself, and our little brother. My dad encouraged Paul to go into therapy to deal with the things he suffered as a child. He and my father spent a lot of time together. He looked up to my dad. He wanted to be like him. He took our last name. He even had ‘Bamba’ tattooed on his body. He said he was half-Puerto Rican and half-Ivorian. Then my father got orders to go to Hawaii and Paul moved to New York. Later on, he liked to say he’d been homeless in New York. He wasn’t homeless; not really. There was a time when he was broke and struggling to pay the rent. He might have been without a place to live now and then. But he wasn’t homeless the way you think of it.

“Paul was a protector. When I joined the military, he was always texting me. ‘You good? Do you need anything?’ He was a ladies man. He liked women, but he liked a lot of women. Women would say, ‘He’s my man.’ No, not from Paul’s point of view, they weren’t. He was getting to a point where he wanted to settle down and have a family. But he wasn’t quite there yet.”

Then Linda echoes what friend after friend says was one of Bamba’s defining characteristics.

“Paul was the most hard-headed individual I ever met. He was driven, stubborn, prideful,” she says. “Because of his childhood, he always felt that had to prove himself and prove people wrong when they looked down on him. He had big dreams and was passionate about what he did. He’d been to hell and back and was planning on traveling further. He would stop at nothing to be successful.”

The people who knew Bamba best describe him as having a big personality and a big heart. People liked him. He had a charming way about him.

“Paul was my friend,” says Thomas LaManna, a fellow fighter and boxing promoter. “He was a great dude. But Paul was Paul. He had a lot of dreams. And he was a stubborn motherfucker. He’d listen to you and then go out and do exactly what he wanted to do.”

Gardea Christian was Bamba’s best friend and later his business partner. Like Bamba, he had served in the Marines. They met after their time in the service and were loyal to each other.

“Paul was an inspiration for a lot of people,” Christian says. “He was determined. He had a drive to get things done. I’m very protective of Paul and his legacy.”

Jason Harris co-founded a creative agency called Mekanism that specializes in brand development. In 2018, he helped Bamba and Christian launch a health and fitness business called Trifecta Strong.

“I advised them,” Harris says. “I created the logo. We got some investors. We were going to open a gym, but Covid happened and we pivoted to a Trifecta app. Then we ran out of money for marketing and advertising, and the business became personal training. Paul had some high-profile clients [including R&B singer and songwriter Ne-Yo] that kept things going. But he still wanted to open a gym.”

Multiple friends and associates recount the setting for what came next.

Paul craved attention … Paul needed money to open a gym … Paul was driven to prove himself … Paul wanted street cred … Paul wanted people to admire him … Paul saw boxing as his way of getting everything he wanted. Boxing would be his stairway to the next level. He had this scenario in his mind and he was going to play it out regardless of what happened.

When Jake Paul brought social-media influencer boxing into the mainstream, Bamba took note. It was a wave that he thought he could ride to bigger and better things.

“[Bamba] began talking about boxing as a means to an end,” Harris says. “He saw what Jake Paul was doing. And his plan was to become an influencer boxer, get well-known, and make big money so he could get the business rolling and open a gym.”

And there was another motivation.

“[Bamba] really wanted to be famous,” Harris says.

But there was a problem. Bamba didn’t have the physical gifts necessary to be a quality fighter.

“There’s an epidemic in boxing,” matchmaker Eric Bottjer says. “And it’s very dangerous. A fighter with extremely limited ability is backed financially, either by himself or someone else. He uses social media to build an image. He fights. A lot of commissions look the other way or don’t even understand what’s going on. But the fighter can get badly hurt.”

A trainer who worked with Bamba sums up his talent. “Paul wasn’t very good and never would be,” the trainer says. “He just wasn’t gifted physically like you have to be to be even an average amateur boxer. He was never gonna win an amateur tournament in New York, not even a novice one. He had a handful of amateur fights. I remember, in one of them, he got knocked out ugly, face first, unconscious.”

A longtime cornerman agrees that Bamba was a limited boxer. “I never worked with Paul but I saw him a lot around the gym,” the cornerman says. “He was outgoing, always respectful. He had a lot of heart, a lot of grit. But some people, you introduce them to boxing and they take right to it. I used to watch Paul sparring. Even after he’d been boxing for a while, he was very novice.”

Bamba moved from trainer to trainer. In 2021, he turned pro and hired Sarah Fina, who works for Dave McWater, one of boxing’s best managers, to book fights for him.

“I liked Paul as a person,” Fina says. “I thought he was a good guy. And he was marketable. But a real boxer? No. Realistically, his lane was the YouTube world. I told him that. I was always real with him. We never had any official paperwork but he wanted my name on [boxing website] BoxRec as his manager. I took it off at one point and he pleaded with me to put it back on.”

On 21 April 2023, Bamba fought Chris Avila in New Orleans and suffered a bad beating en route to a 40-34, 40-35, 40-35 defeat. That was the last fight Fina made for him. As 2023 drew to a close, he was a club fighter with a 5-3 professional record.

Putting those numbers in further perspective; the three fighters Bamba had lost to had a composite ring record of three wins against nine losses at the time he fought them. Looking at the fighters he did beat; three of them now have a composite ring record of 0 wins against 19 losses. The fourth has a 2-13 record. And the fifth has won one of his last 17 fights.

Bamba was fighting as well as he could. But he wasn’t good enough to succeed even as a club fighter. So he opted for a new strategy.

And “the knockout streak” began.

It’s a common (and legal) practice in boxing for managers to “buy” bouts on fight cards for young prospects. The manager reimburses the promoter for the purse paid to both his fighter and the opponent. Other fight-related expenses, such as travel, are also reimbursed. The opponent is overmatched and has little chance of winning. But the opponent does try to win and occasionally pulls off an upset.

There are also instances where a fighter is matched against a “professional loser”.

“This is how it works,” Jason Nesbitt, who finished his career with 10 wins, 197 losses, and four draws, told writer Mark Turley. “Before we go out there, I get a quiet word in my ear. ‘Jase, you’ve got to take it easy. This lad’s sold six grand worth of tickets, so we can’t have him losing. If you go out there and knock him out, I promise you, you’re not getting any more fights.’ I’m not actually trying to win because I’m told not to. And that’s basically what I do to earn my money in boxing. It’s my weekly wage, so I’m going to do what I need to do to keep it coming.”

Bamba was neither young nor a prospect. He had begun his career with “real” fights. Then, to fuel his dreams, he moved to questionable ones.

Bamba’s first 11 “knockout victories” in 2024 took place in Latin America, eight of them in Colombia.

BoxRec is the closest thing to an official record-keeper the sport has. John Sheppard created and oversees the website. He does his best to maintain the integrity of the site. But “integrity” and boxing don’t always go hand in hand.

Sheppard says that, from 2018 through 2020, there were roughly a dozen fights a year in Colombia that involved a boxer from the United States. In 2024, that number had risen to 278. And according to reports submitted to BoxRec, the American fighter won all 278 of those bouts. These numbers speak for themselves. Sheppard calls the practice “win tourism”.

“Win tourism is the same business model wherever you find it and there’s complicity at every level of the sport,” Sheppard says. “We’re record-keepers. We’re not Interpol. We try to keep accurate records but we can’t police every boxing match around the world. A few years ago, we started cracking down on some of the results coming out of Mexico. We were successful to the extent that the number of reported fights involving an American against a non-American in Mexico was cut in half and the win percentage for the non-American fighter doubled. But it’s hard to make progress. Some people who work at commissions look the other way or worse. And some are scared. Two Mexican commissioners who were working with us had funeral wreaths delivered to their homes.”

“Some people make good money from it,” Sheppard continues. “Most of it probably goes to the promoters. The so-called opponent gets something. Sometimes they put one fighter in the ring and use another fighter’s name for a fee. Sometimes they don’t even have the fight and just report a win for a particular fighter.”

Bamba’s knockout streak began in Santa Marta, Colombia, in January 2024, with two reported fights in less than a week. On three occasions in 2024, he was listed as having fought twice in Colombia within a span of six days or less.

“As far as I know,” Fina says, “Paul booked all the fights he had last year himself. I had nothing to do with them.”

Christian supports Fina’s version of events, saying, “Paul represented himself in negotiating his fights. He had contacts with promoters. I didn’t go to his international fights but I dealt with a lot of the logistics like setting up the travel.”

Christian also says that an average trip to Colombia cost about $5,000 all inclusive and that he helped finance the trips through the business he ran with Bamba. Asked whether the fights were fixed, he answers: “Paul got in the ring with fighters. There were crowds. He hit and got hit.” Pressed for more detail, Christian says, “I’ve seen guys fight and it looked to me like a guy wasn’t fighting. I never had any doubts about Paul’s opponents.”

But others have a different view.

“From what I heard,” says a trainer who worked with Bamba, “in a lot of those fights, Paul knew the other guy was coming to lose and would quit on his stool.”

Someone who was on site for one of Bamba’s fights in Colombia says, “Paul knocked his guy out. And I remember thinking: ‘No way.’”

A cornerman who worked with one of Bamba’s opponents gives further context, saying, “Some guys aren’t fighting to win. They’re fighting to feed their families. They don’t care about their record. They need the money. Put yourself in that position. People don’t like to talk about it. They pretend it’s not happening. But it is. Bamba wasn’t much better the year he won all those fights than he was the year before. But it was like building a house. If you have the money to pay for it, you can build the house any way you want.”

Did Bamba know that some of his fights were fixed? Three people who knew and liked him offer their thoughts.

“Paul was a fighter. When a fighter is in the ring, he knows whether or not someone is trying to hurt him.”

“I’m sure that some of the guys Paul fought were so unskilled or so far gone that they had no chance of winning. But some of the others would have beaten him in an honest fight. And it’s hard to believe that Paul was so delusional that he thought all of the guys he was fighting were trying to win.”

“Of course he knew. Someone had to set things up.”

On 19 October 2024, Bamba fought in the United States for the first time since his knockout streak began. The opponent was Francisco Cordero (listed on BoxRec as born and living in Colombia). The fight took place in New Hampshire, a state with minimal regulatory oversight for boxing. Bamba was required to submit the results of bloodwork taken within the previous six months (to check for hepatitis), an eye examination and an EKG (both taken within the previous year), and to undergo a cursory physical examination before the fight. He knocked Cordero out in the third round.

Michael Reyes was the promoter for Bamba v Cordero.

“It was a paid-for fight,” Reyes says. “Bamba’s team got in touch with me and paid for everything. Travel, lodging, the opponent’s purse. They chose the opponent. There was a slot fee to get on the card. Typically, I get $500 for that. The only reason he was on the card is that it was a paid-for fight. He wasn’t selling any tickets. No one was traveling to New Hampshire to watch him fight. The contract said his purse was $1.”

“He seemed like a nice guy,” Reyes continues. “He was polite. Our interaction was pretty much, ‘Hello. How are you? Thanks for coming.’ There was nothing else one way or the other that I remember about him. When it’s my event, I’m so busy that, unless it’s a fighter who’s directly connected to me, I might not even watch the fight. I don’t remember watching this one.”

Two weeks later, Bamba fought again; this time in Alabama, another state with minimal regulatory oversight. The opponent was Colombian-born Santander Silgado Gelez who lives in Florida. Bamba was credited with a sixth-round stoppage.

“Paul was introduced to me by a promoter in Mississippi who was a friend of a friend of a guy who promoted with me,” says Dexter Sutton, who promoted the fight. “Paul wanted to buy a spot on the card and we sold him the spot for $300. Paul did all the arrangements for the opponent and took care of all the expenses. All we had to do was make sure the fighters got their bloodwork and everything was OK with the commission. Alabama isn’t as strict as some other places with the physicals.”

Sutton continues: “I thought Paul was a nice guy. He had somebody with him that worked his corner. We had the normal conversation. ‘How was your trip? Welcome to our promotion.’ The opponent fought pretty much like he came for a payday. It looked like Paul carried him for a few more rounds than it could have been. Then the other guy just quit. Later on, I heard Paul died and I wanted to send flowers to his funeral. But when I contacted the people who put him in touch with me, they never got back with where to send the flowers.”

There’s no indication that Reyes or Sutton did anything improper. They were following the laws of the states in which they did business.

Meanwhile, there’s no way to know how many of Bamba’s final 14 fights were honestly fought. But statistics and the available video suggest that a significant number of them weren’t. That brings the narrative to Bamba’s final fight on 21 December 2024, in Carteret, New Jersey against Rogelio “Porky” Medina Luna.

Medina is a 36-year-old journeyman who entered the ring for his fight against Bamba with a 42-10 record that included 36 knockouts. There was a time long ago when he was a prospect with 23 wins in 23 fights. In recent years, he has been a stepping stone for big-name fighters such as Gilberto Ramírez, David Benavidez, Badou Jack, James DeGale and Caleb Plant. The prevailing view among boxing insiders was that Bamba was nowhere near Medina’s level as a fighter.

Bamba v Medina was designated as a fight for the World Boxing Association ‘gold’ cruiserweight championship. The WBA isn’t known for the validity of its championship processes. At present, it recognizes 43-year-old Kubrat Pulev as “heavyweight champion of the world” – a distinction that Pulev earned last December when he defeated 40-year-old Manuel Charr, who underwent double hip replacement surgery in 2017.

“Thomas LaManna set it up with us,” says Alex Barbosa, who promoted Bamba v Medina. “Thomas also worked things out with the WBA. We didn’t have to pay Paul. Paul and Thomas paid Rogelio’s purse and all of the other expenses associated with the fight. That’s standard practice these days. And Paul was super nice. We never had any problem with him. He was a good guy.”

LaManna explains more. “Paul wanted to do his thing,” he says. “It was pretty simple to put together. The sanctioning fee we paid the WBA for the gold belt was $25,000. That was the big expense. You had Medina’s purse, some travel and other expenses. Paul had financial backers and sponsors who covered most of it. He sold some tickets. It was a common boxing deal structured so Alex wouldn’t lose any money on it.”

On 12 November 2024, Bamba posted on X: “12/21/24 I’ll take on my biggest challenge and fight for the opportunity to live my dream.” On 15 December he posted again: “6 days till my 14th fight this year. WBA GOLD Cruiserweight World Title. I have sacrificed this entire year and have given everything I have to boxing.”

Bamba v Medina was a dreary outing. At the end of round six, Medina told his corner to stop the fight, saying that he had leg cramps.

A veteran trainer who was at the fight says, “Paul got hit with some big punches. I remember his head snapping back a lot. But each time Porky hit him, he backed off and didn’t press the action. And then Porky quit on his stool. From where I sat, it looked like, if Porky came to fight, it would have been a different story.”

“I was there,” says another boxing veteran. “And if you knew what you were watching – to me, at least – it didn’t add up. The whole fight didn’t seem right.”

LaManna worked Bamba’s corner that night. “Paul’s regular trainer couldn’t make it,” LaManna says, “so someone else was the chief second and I helped out. I thought Paul would do better than he did in the early part of the fight. But as it went on, Porky faded.”

“How good a fighter was Paul?” LaManna is asked.

“We could all be better,” he says.

“There was nothing crazy in the fight,” Barbosa adds. “Paul didn’t take any ‘Oh my God’ punches that I saw. I wasn’t surprised when Rogelio stayed on his stool. You can see it in a fighter’s face when he doesn’t want to continue.”

Then Barbosa is asked the same question as LaManna: How good a fighter was Paul?

“You’re as good as your record says you are,” Barbosa answers. “And Paul’s record was pretty good.”

Bamba v Medina is available on YouTube. Readers can watch it and make their own judgment as to the merits of the fight.

In the dressing room after the fight, Bamba was ecstatic. “If Jake Paul wants to take boxing seriously,” he proclaimed, “I’m probably the first call he’s going to make. If he wants to do something real, I’m right here.”

“That was the goal,” Christian says. “Almost from the start, getting a fight against Jake Paul was the goal of everything,”

If Bamba v Jake Paul had happened, it would have been an ugly beatdown. Jake Paul has become a solid club fighter; Bamba wasn’t close to that level. But fantasies aren’t bound by the same rules as reality.

“Tonight I accomplished a goal I set out with this year,” Bamba posted on X after the Medina fight. “14 fights 14 KOs. Thank you to everyone who’s been behind me. Truly grateful for anyone who’s breathed belief into me. The redemption arc is finally over and big things are on the horizon for 2025. THANK YOU ALL!”

On 22 December, Bamba posted again on X: “Possibly will be fighting on New Year’s Eve in Dubai. Might be able to hit 15. Huge announcement coming.”

It wasn’t to be.

Six days later, the news spread from friend to friend: Bamba had died in his sleep.

There was an autopsy. No official statement regarding the cause of Bamba’s death has been released. The most common belief among his friends is that he died as the result of a brain bleed. But whatever the cause, Bamba is dead. And his friends are sifting through their memories.

“I went to Paul’s last fight,” Fina says. “And it was the same story as most of his fights. It was competitive, which it shouldn’t have been. Paul took a lot of unnecessary punishment. He texted me after the fight. It was the last text I ever got from him.”

Bamba’s text to Fina read, You still think I suck, don’t you?

Paul Bamba died in his sleep on 27 December 2024, at the age of 35. There were clear signs before then that his health was in jeopardy.

There’s no good way to get hit. And Bamba got hit a lot. He was hit in the gym. He was hit in fights even when there was an understanding that he would win. For a while, he was a paid-by-the-round sparring partner. They take a beating.

“I told him to slow down,” Fina says. “He never took a break. He never gave himself time to heal. He was fighting way too much and taking much too much punishment. But Paul did what he wanted to do. There was no saying ‘no’ to him.”

The most troubling documentary evidence relating to Bamba’s medical condition is a 25 July 2023 letter written by a neurologist, Dr Alina Sharinn. Bamba’s last fight prior to the letter being written was his 21 April 2023 beatdown at the hands of Chris Avila. He was scheduled to fight Anthony Taylor in Tennessee on 22 July but the fight was cancelled. Then Paul posted Sharinn’s letter on social media.

The letter read in part, “Mr Bamba has suffered a concussion and an episode of traumatic diplopia [double vision] within the past year and now presents with increasing headaches. His MRI of the brain revealed white matter changes in both frontal lobes. At this time, I discussed with Mr Bamba to stop boxing temporarily as well as to avoid any other activity that can produce head trauma. He will be reevaluated in 4-6 weeks.”

Why did Bamba post the letter? Who knows.

Then, in a 28 July video post on X, Bamba declared: “The first thing we’re gonna go over is the medical itself. She said she wanted to take a second look. She said there’s signs of early onset trauma. Is there anything I want to tell her. So as soon as she said ‘early onset trauma,’ I was like ‘trauma?’ And she said ‘brain trauma’. So I said ‘Oh!’ That freaked me out. I can’t lie. I have a bunch of twitchin’. I got headaches. It was scary to hear it. It’s brain trauma, bro. It’s a lot different from just some bullshit. I’m not gonna get too deep into my health. But there’s a few things that are alarming.”

Nitin Sethi is a neurologist and the medical director for the New York State Athletic Commission.

“A lot of people have white matter changes,” Sethi explains. “It’s most common in older people and can result from hypertension, diabetes; there are many possible causes. But this was not an older person and it’s certainly possible that the changes were related to boxing. So what you have to do is compare MRIs over time, look at the differentials, and then decide whether to say, ‘That’s it. No more. We won’t license you to fight.’ At the very least, it’s a red flag.”

Dr Margaret Goodman, also a neurologist, founded the Voluntary Anti-Doping Association (Vada) to combat the use of banned performance-enhancing drugs in boxing and is one of the foremost advocates for fighter safety in the United States.

“I agree with Nitin,” Goodman says. “Based on this letter and the fighter’s history, it certainly looks as though the fighter was at increased risk of serious injury and shouldn’t have been allowed to fight again without a serious medical review.”

But there was no serious medical review because Bamba brought his career to jurisdictions where there was little if any regulatory oversight. He fought next in Colombia on 25 January 2024, which was when his 14-fight knockout streak began.

The details around Bamba’s final fight, held in New Jersey, are particularly troubling.

“Before that fight,” one of Bamba’s friends says, “he was complaining to me about headaches. He said: ‘My head is killing me.’ I told him: ‘Look, if your head is hurting, slow down. Get checked out.’ But he wouldn’t listen to anybody. He did what he wanted to do.”

The New Jersey State Athletic Control Board (NJSACB) is thought of as having high medical standards.

“A lot of people have questions about how Paul got approved for that fight,” a well-respected trainer says.

Larry Hazzard, the commissioner of the NJSACB, declined comment when asked about Bamba. Instead, a public information officer for the New Jersey Attorney General’s office told the Guardian that “Mr Bamba fulfilled both the license and medical requirements and was granted clearance to compete in Carteret on 21 December 2024.”

In that regard, matchmaker Eric Bottjer, who keeps an eye on these things as part of his job, says, “There was a show in New Jersey earlier this year where phoney medicals were submitted to the commission for three fighters [two bloodwork and one MRI]. It’s being looked at now.”

After Bamba’s final victory, his publicity machine went into overdrive, claiming that his 14 knockouts in 2024 had broken Mike Tyson’s mark for most consecutive knockout wins in a calendar year. Even if all of Bamba’s wins had been legitimate – which they weren’t – that claim would have been inaccurate. Mike Tyson had 15 fights in 1985 and won all of them by knockout. But we live in an age in which, if something is repeated often enough, it’s accepted as true no matter how false it might be. Many of the obituaries written about Bamba in mainstream publications cited his “knockout record”.

Bamba’s friends speak of him with fondness.

“He was determined to make something of himself,” Harris says. “He was passionate about chasing the impossible. He was determined to achieve what he considered success. He was relentless. That caught up with him in the end. But he will always be a motivating force in my life and the lives of many, many others.”

But there was a downside to what Bamba did. He deserves respect for what he accomplished as a 5-3 club fighter who got in the ring and fought as honestly as he could. The fixed fights he had after that – and some of them were fixed – tarnished his legacy. There were times when he punched other men in the head and tried to hurt them with the understanding that they would not try to hurt him back. Some of those men – who were human punching bags – are likely to have suffered brain damage too.

Fighters also have to take responsibility for their own physical wellbeing. And Bamba didn’t do that. He recklessly put his own life at risk.

Bamba’s sister, Linda, puts his life in perspective.

“To the very end,” Linda says, “Paul would ask our dad, ‘Are you proud of me?’ But we were all proud of Paul for getting to where he was in life before boxing. Boxing was about how Paul felt about himself. Nobody who loved him would have loved him less without those fights. I didn’t go to his fights. It scared me. I didn’t want to watch him get hit. Before the last fight, I knew he was hurting. His head hurt really bad. But it was, ‘Let me just get this win. Let me just win this championship.’ It wasn’t till after we got the postmortems that I understood how bad things were. Someone should have said, ‘Slow down. This isn’t normal. This is dangerous. Your life comes first. You don’t have to keep doing this. We love you and we’re proud of you with or without boxing.’ I wish I’d asked more questions about what was really going on. It sucks that Paul’s life was cut short. It really sucks.”